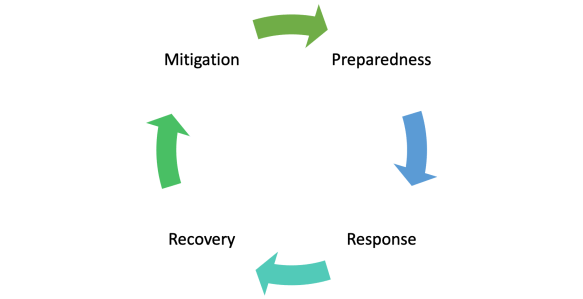

Earlier in my career I had the opportunity to work as an instructional designer on courses related to disaster preparedness and response. These courses were designed to help train healthcare professionals for their role in handling situations that might result in mass casualties, like floods and earthquakes. Through that work (which, to be honest, I never thought would converge with my life as a faculty member) I was introduced to the disaster management cycle.

At the top of the cycle, you see mitigation and preparedness, both of which are focused on risk management. At the bottom are response and recovery, the parts of the cycle that are triggered into action by an actual disaster or emergency that has occurred. Response is what happens in the immediate aftermath, when people scramble to assess the situation, save lives, and keep critical services running. It’s a period of quick problem solving and temporarily solutions designed to patch people through the worst of the emergency. Recovery, then, is the phase that focuses on developing sustainable solutions and finding the new normal. Response and recovery tend to be concurrent processes for a period of time, although recovery is a long-term project in most settings.

So, what does this have to do with education? I’ve found the emergency management cycle to be a useful lens for thinking about education amid the COVID-19 crisis. During the Spring 2020 term, we were clearly in response mode. At my university, we had a week of lead time (spring break) to shift our classes to a remote format. Shifting to remote was not as simple as posting materials online or delivering lectures in front of a webcam instead of a classroom (and I don’t mean to imply that these were simple tasks for everyone). Decisions had to be made about tools and pedagogy. Student situations and needs had to be considered. Assessments had to be reworked. Stress levels were rising due to fear, uncertainty, economic struggles, and isolation. Working with small children or other family members around proved difficult. Everyone did the best they could, but this definitely was not a time for award-winning teaching and learning.

As we move into summer, for those of us teaching this term, and/or consider the upcoming fall term, it’s really time to think about recovery in the classroom. I’m talking about short-term recovery, starting for some folks in summer, and others in fall 2020. We still have a lot of uncertainty that lies ahead of us, but in the upcoming terms we will able to plan and execute remote instruction by design, not just react to remote instruction as an emergency response.*

The Pedagogical Disaster Management Cycle and COVID-19

Some of the big differences that we’ll see as we find ourselves moving into recovery, with classes that are remote by design, include the following areas:**

- Opting in.When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down universities, most schools were in the middle of a term. Even schools that were wrapping up a quarter or a short term still had a segment of the regular academic year to complete. Students had already committed themselves to school for that term or academic year. Tuition was paid, plans were made, and the only real option was for students to complete the term remotely. Students and instructors didn’t sign up for Spring 2020 remote education. However, in Fall 2020 remote learning will be a choice for students. They can opt in to take classes, knowing these classes will be remote from the start or may shift to a remote mode if there is a new outbreak. Alternately, they can opt out. Even when remote is not the preferred option, opting in is sure to be better received and an overall better experience than an emergency pivot into the unknown.

- Developing relationships.When we shifted to remote education in the middle of a term, instructors were able to ride out the senses of community, trust, and goodwill that their classes had already generated in the classroom. That won’t be possible for instructors who start the term remotely. Instructors and students won’t be able to capitalize on pre-existing classroom relationships. They won’t be visualizing each other in the classroom, but instead will find themselves interacting remotely with strangers. Instructors are going to need to establish identity and presence for themselves, and to encourage students to do the same. In many courses, they’ll want to build a sense of community and interdependence among learners.

- Setting a rhythm for learning activities and expectations. Instructors will need to think about how time flows differently outside of a physical classroom, especially in situations where asynchronous instruction, compressed course timelines, and hyflex models are used. Students are often used to coming to class and being told what to do before the next class. That approach won’t work remotely, and students taking multiple remote classes may struggle to manage their time effectively. Instructors need to provide guidance for students on how to structure their course-related activities under these models, and set expectations for how much time will be spent on different activities on a daily or weekly basis.

- Engaging learners remotely. As the spring term, most of us were just trying to get through it and survive, finishing out a course plan to the extent possible. At many institutions, the bulk of the semester was already over, anyway. However, with a full term of remote learning, instructors will be challenged to find ways to engage learners. Building community and setting a rhythm for a course is the first step, but then the activities that learners are asked to engage in will need to be worthwhile ones. Students are more likely to keep up with class and immerse themselves in learning if they feel that their instructor will miss them. It’s pretty simply: students show up and participate in activities that can’t be easily made up later. The flip side of that scenario is true as well. Instructors will feel more engaged in classes when their students show up and participate. In recovery, it’s time to learn how to foster this type of engagement.

- Knowing the tools. Right as we made the shift to remote instruction, a lot of “how to use the tools” workshops sprung up. They were necessary. There were instructors who didn’t know how to use their LMS or conferencing tools, and there were others who used those tools already, but not in ways that support remote instruction. These folks experienced a technology learning curve under stressful conditions (as did their students). There were plenty of technology fumbles in the initial shift to remote learning, but perhaps we can reframe those fumbles. They were the pilot test for what comes next. Instructors have learned new tools and features, and probably have a good sense of what they would like to do but couldn’t accomplish this past spring. During recovery, more thoughtful and purposeful selection and use of tools is possible. And really, none of this is about the tools themselves, but rather about having the right tools to connect to students, build learning relationships, and deliver/explore learning content.

- Developing reasonable and appropriate remote assessments. Some assessments planned for in-person classes did not easily shift to remote classes, for a whole host of reasons. Instructors modified assessments on the fly because students lacked access to necessary resources, proctoring tools were uncertain or unavailable, interactions were unpredictable, and everyone was just stressed and worn out. In recovery, we have the opportunity to proactively modify or develop assessments that will work for our students under remote conditions.

- Having a backup plan. Back in January 2020, who thought to themselves “better have a backup plan in case a global pandemic shuts everything down”? Who had even used the term remote teaching/learning? Right. None of us. But now everyone in higher education is well aware that backup plans are needed, and has a sense of what it looks and feels like when everything changes in the middle of a term. In the fall, classes that start out remote will likely remain remote, but classes that start out on campus should have a backup plan should it become necessarily to quickly shift to remote learning. That plan can be proactively in place (this ties back to the preparedness part of the cycle) so everyone knows what will happen if a stay at home order is suddenly enacted. [Those of us who live in hurricane territory already have these plans in place for our fall term courses. We’ve had to say to our students: If you don’t have power next week, don’t panic. Check in as soon as you are able and let me know what your current status is.]

At the end of the Fall 2020 term, if it has been a successful period of recovery, we will learn from our experience with remote-by-design learning. Instructors will have more confidence and ability with remote teaching methods, and these skills will likely strengthen their abilities as classroom teachers as well. Students will have more experience with remote learning, which may translate into valuable lifelong learning and self-regulation skills. And institutions may become more flexible and collaborative, with everyone working together to promote success (or at least will have some good insights into what needs to be done for future mitigation and preparedness).

I know, I know … this all sounds a bit pollyannaish in the midst of a situation that really feels quite awful all around. The reality is that recovery will not be easy, nor will it be perfectly done, but the individuals who learn throughout the process can help shape the new normal. Those who fight it may find themselves disappointed if recovery becomes a long, drawn-out process, or if the new normal does not look entirely like our pre-COVID lives.

*All of this is a lot of work for instructors, who may be struggling to get work done with small children at home, who may be dealing with anxiety related to the situation, and who . I’m not going to get deeply into this topic right now, but I didn’t want to write this whole post about what is possible during recovery without acknowledging the labor that is involved in doing it well. Institutions can’t expect instructional excellence without investing in it.

**There are various ways of addressing these issues, all well established in the online/distance learning literature. I plan to write posts on these topics in the near future, with some practical tips and examples.

Obviously you are very well versed in distance learning/online education. Do you think after this that schools are going to struggle to bring students back into the classroom? It has been over 30 years since I have been in a college classroom but can see that this could become a finacial issue for many schools.

LikeLike

Thanks, Bayraider. Schools will have financial issue to grapple with, for sure.

I don’t think that this experience will lessen the demand for on-campus learning and experiences in the future, but I hope it will result in instructors and students who are more adept at using technology to communicate and support their learning experiences, no matter the modality.

LikeLike